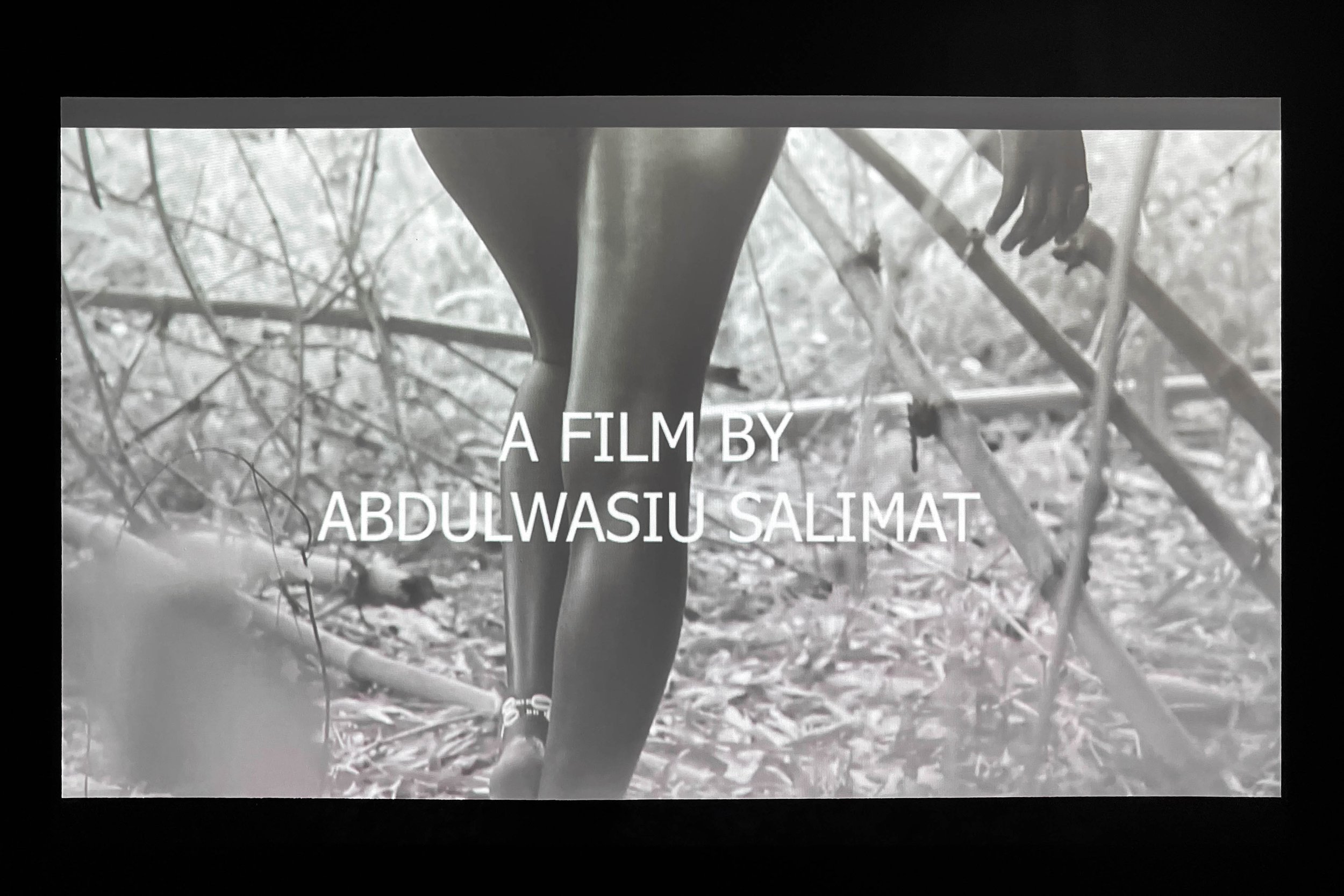

Dialectics of Fugitivity

Abdulwasiu Salimat and Simone Chnarakis

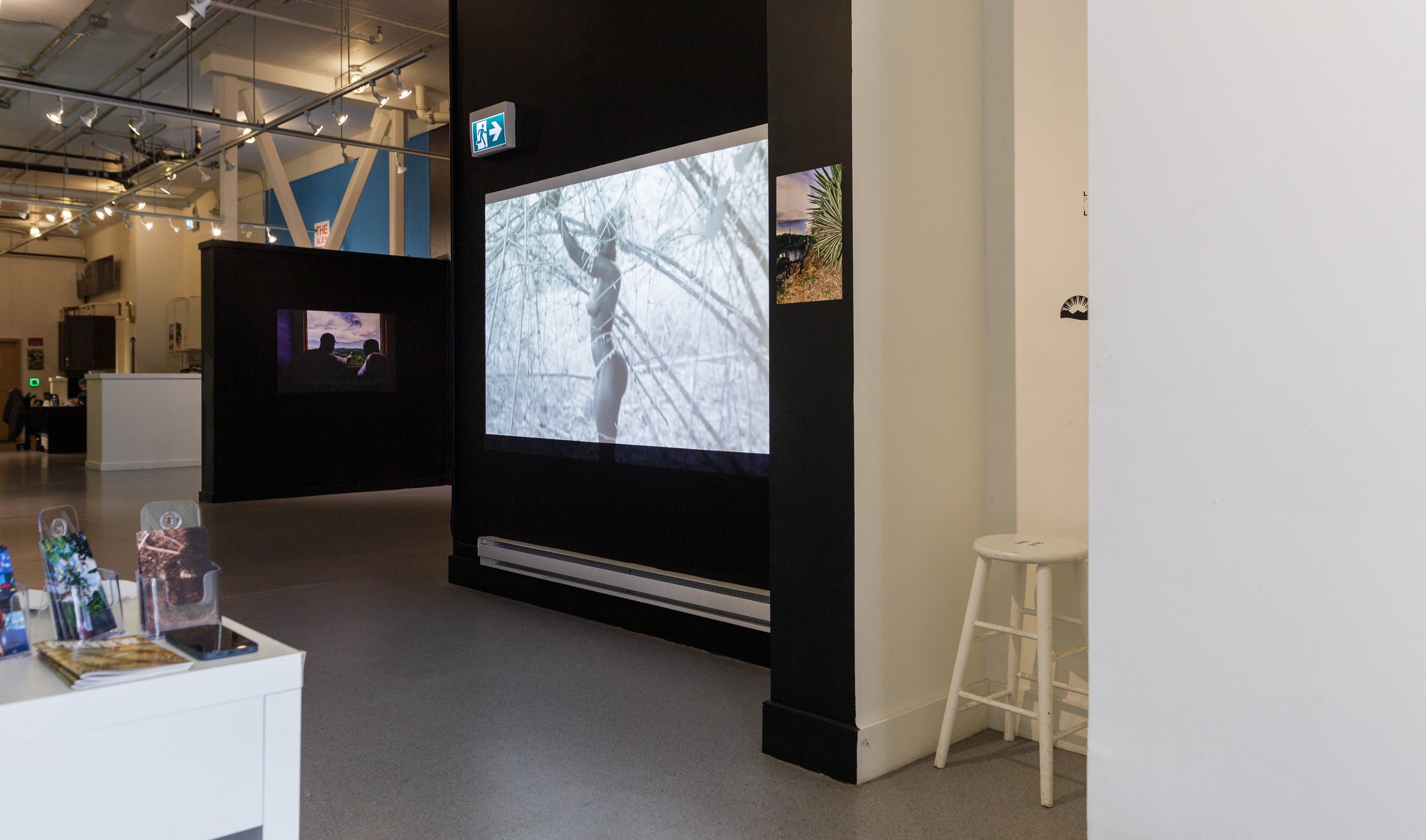

Dialectics of Fugitivity

Running April 8**, 2023 to May 20, 2023.

“That all attempts to repress Black people’s right to gaze has produced in us an overwhelming longing to look, a rebellious desire, an oppositional gaze.”- bell hooks, The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.

Nigeria gained independence from its British colonizers in 1960, after 60 years of colonial rule and a century-long exploitative relationship with the West. Shortly after Nigeria gained its independence, Jamaica was emancipated from British colonial rule in 1962, after a 300-year-long draconian relationship with British colonizers. This span of time included the genocide of the Indigenous peoples of Jamaica, The Arawak people, which resulted in the forced dislocation and enslavement of African bodies, some of whom incidentally trace their ancestry back to Nigeria. Although Nigeria and Jamaica were exploited in different ways, the lasting impacts of their colonial exploitation remains jarringly similar. In post-colonial Nigeria and Jamaica, a constant topic of contest revolves around how these nations and their inhabitants could construct a post-colonial & post-modern and national & personal identity that subverts the constructed narratives of Black nationhood and Black identity imposed from an exploitative colonial gaze.

In Dialectics of Fugitivity, exhibiting artists Abdulwasiu Salimat and Simone Chnarakis utilize their lens-based practices to explore the power of looking and the possibilities of refusal and futurity that occurs when Blackness enters the frame. For Chnarakis and Abdulwasiu, Blackness is considered fugitive; the Black subjects in their images are emblematic signifiers of the current and future state of Blackness that subvert a gaze from elsewhere that attempts to define their embodiment.

In the history of the West, and more specifically the history of modernity and technological innovation, instruments constructed by white bodies, and heralded as tools for the new dawn for humanity, were tools used to oppress and dispossess the bodies of the other. The camera is an example of one such instrument, posed as an objective tool to define our shared reality but instead used by white bodies to define the other and provide a rationale for European colonial conquest and the subsequent/ongoing exploitation of the other. In recent years, Black bodies have begun to reclaim the camera and use images to document their nuanced realities while also problematizing the notions of Blackness disseminated in visual culture constructed by a venal white gaze.

In this exhibition, the Black female gaze is upheld and vindicated. In bell hooks’ writing on Black feminism and the power of looking, she explains that looking acts as an inflammatory gesture of resistance that confronts the hegemonic epistemological order. hooks further notes that alongside the confrontation of a hegemonic gaze that occurs when Black women look back, there is a possibility to envision an alternative state of being to our shared reality constructed by the bodies who live at the margins of our societal status quo. Thus, the artists in this exhibition not only visualize the possibilities of Blackness outside of an ever-pervasive white gaze, but also reference their current realities and invoke a distinct sense of agency and Black identity that make themselves present in the frame.

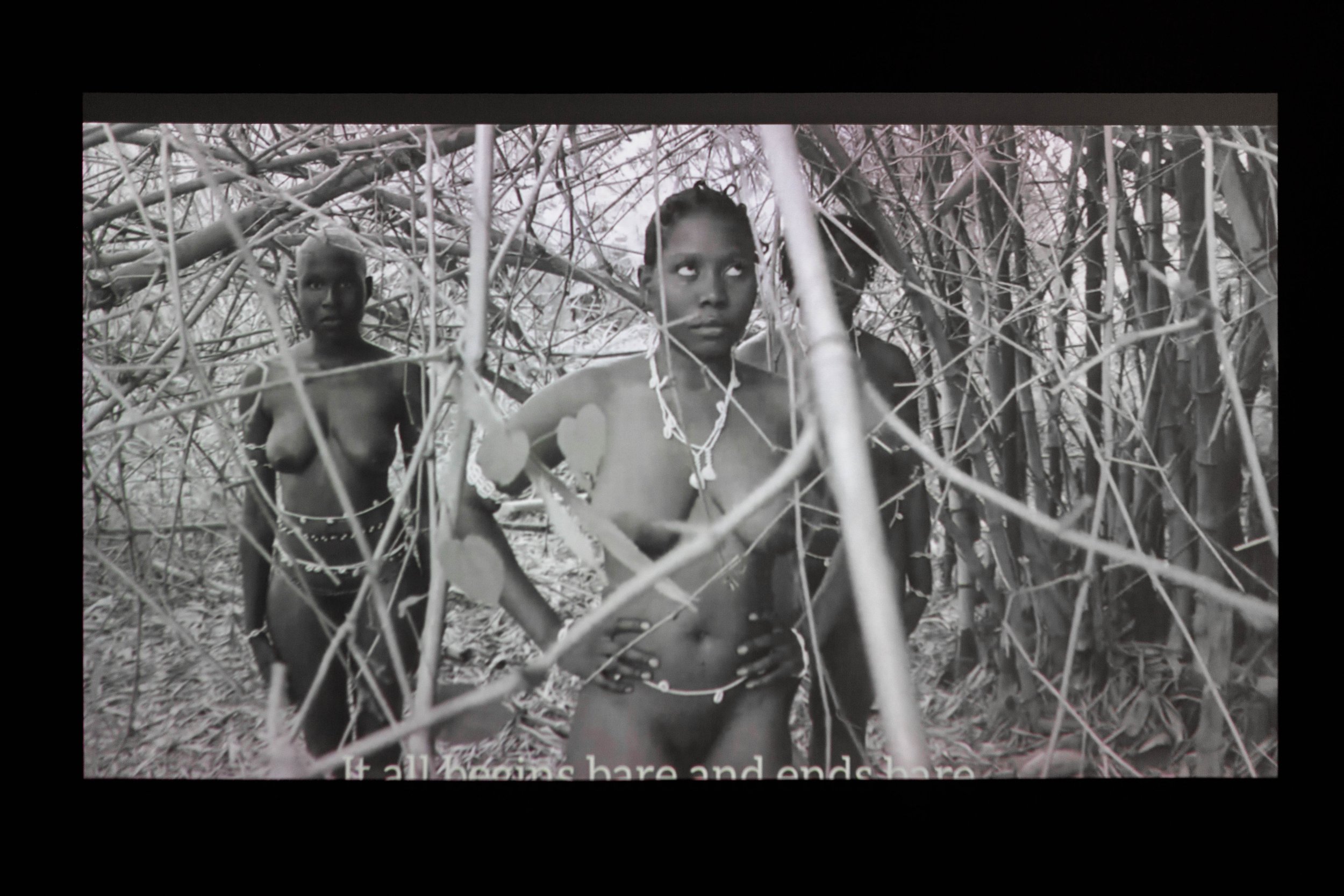

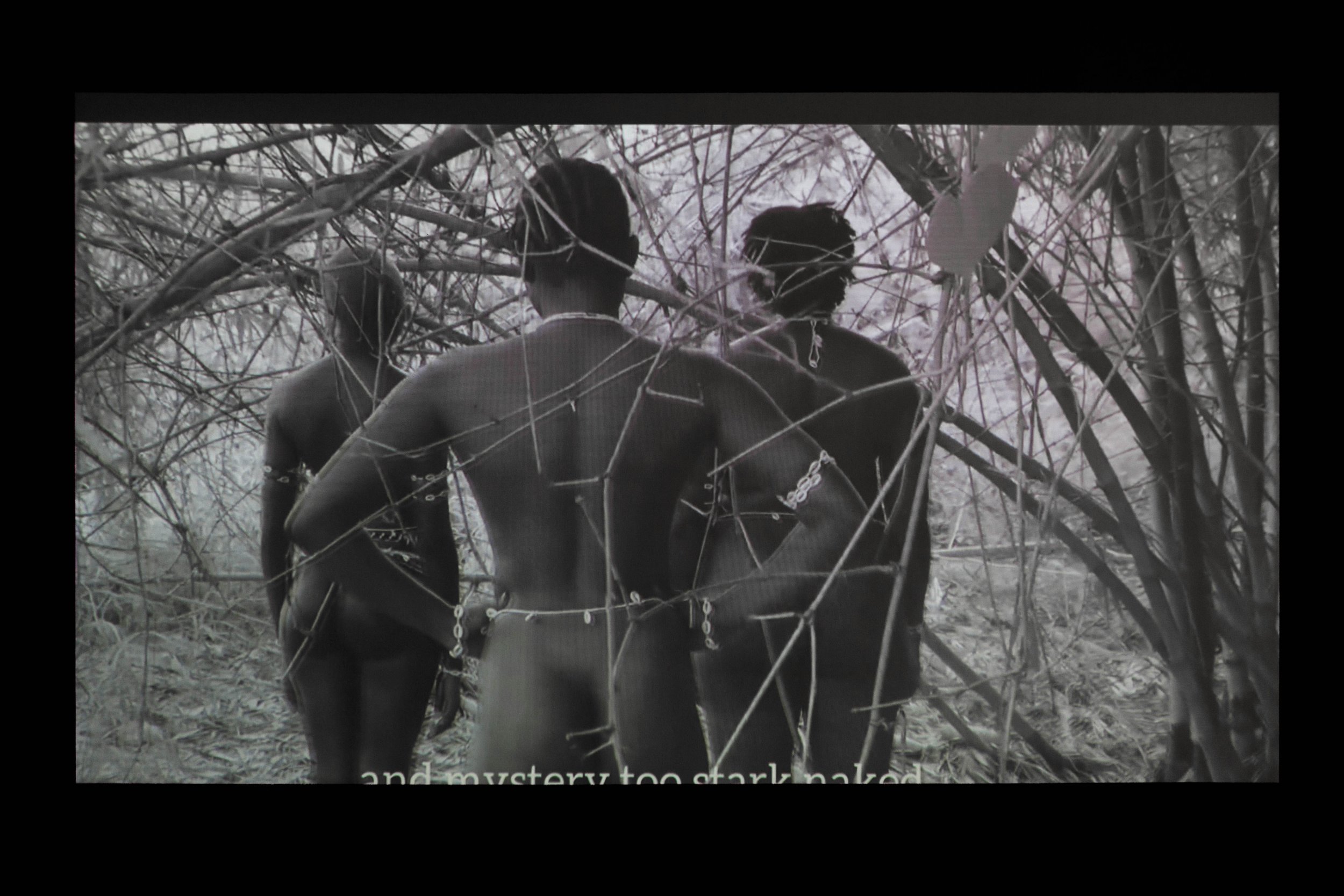

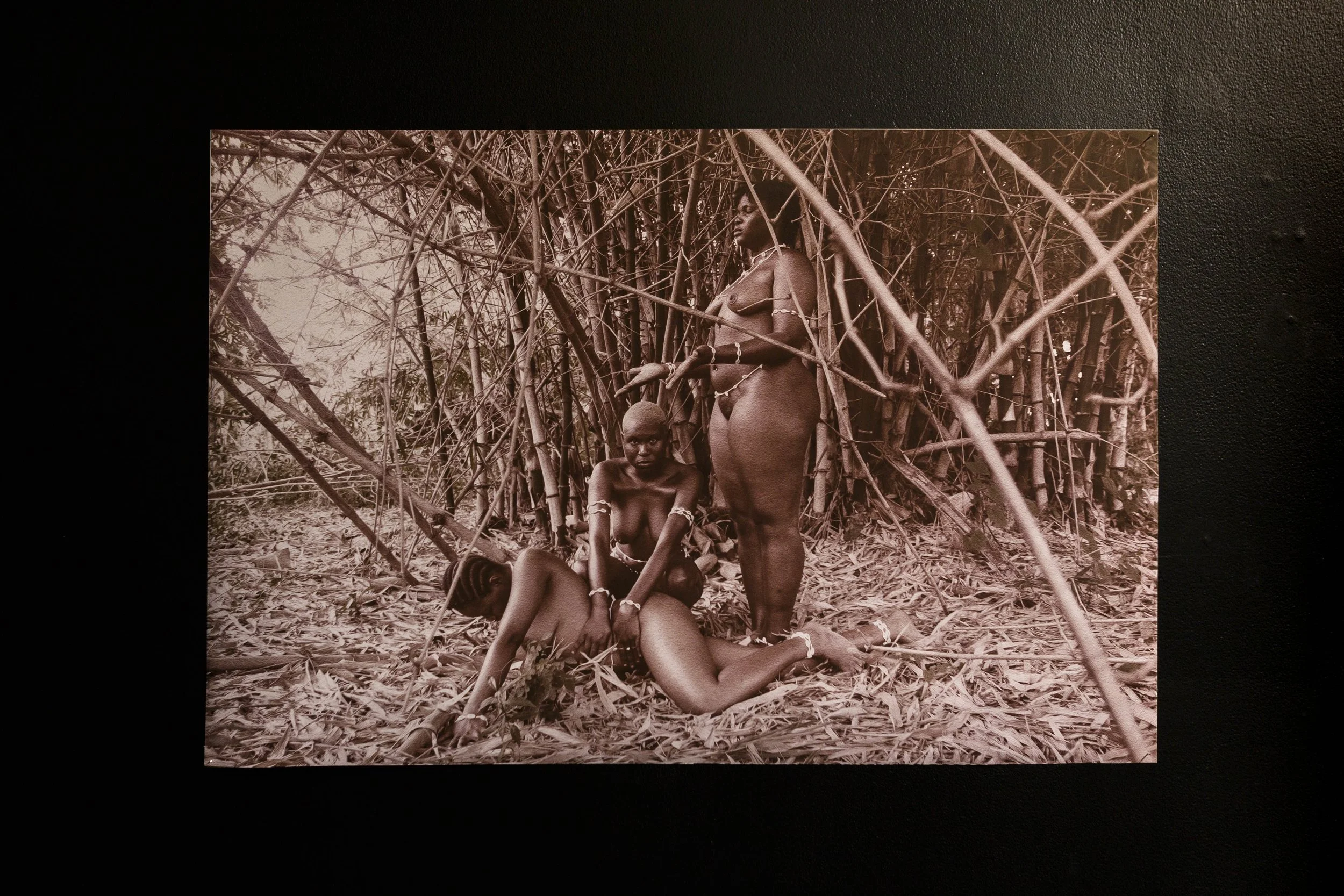

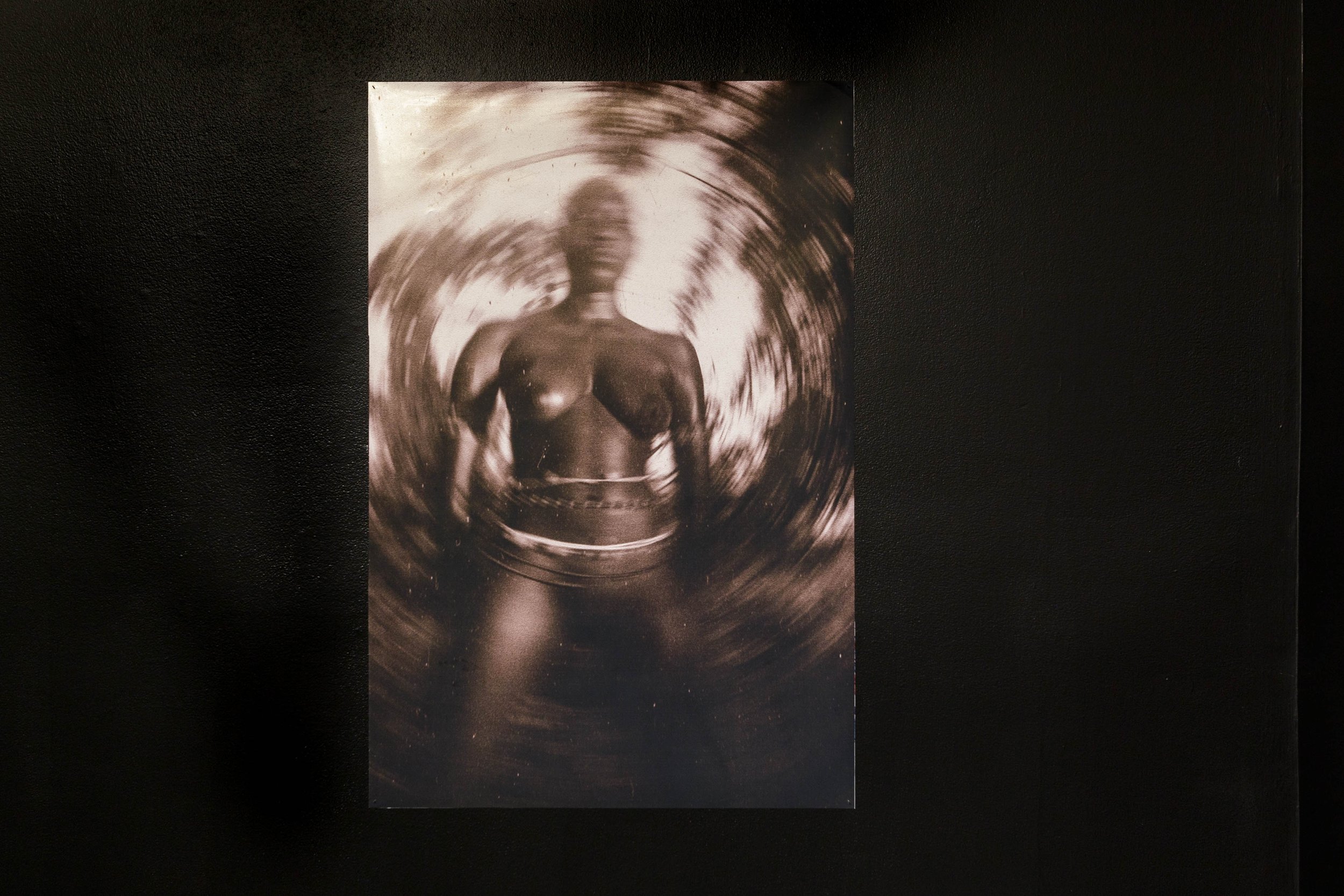

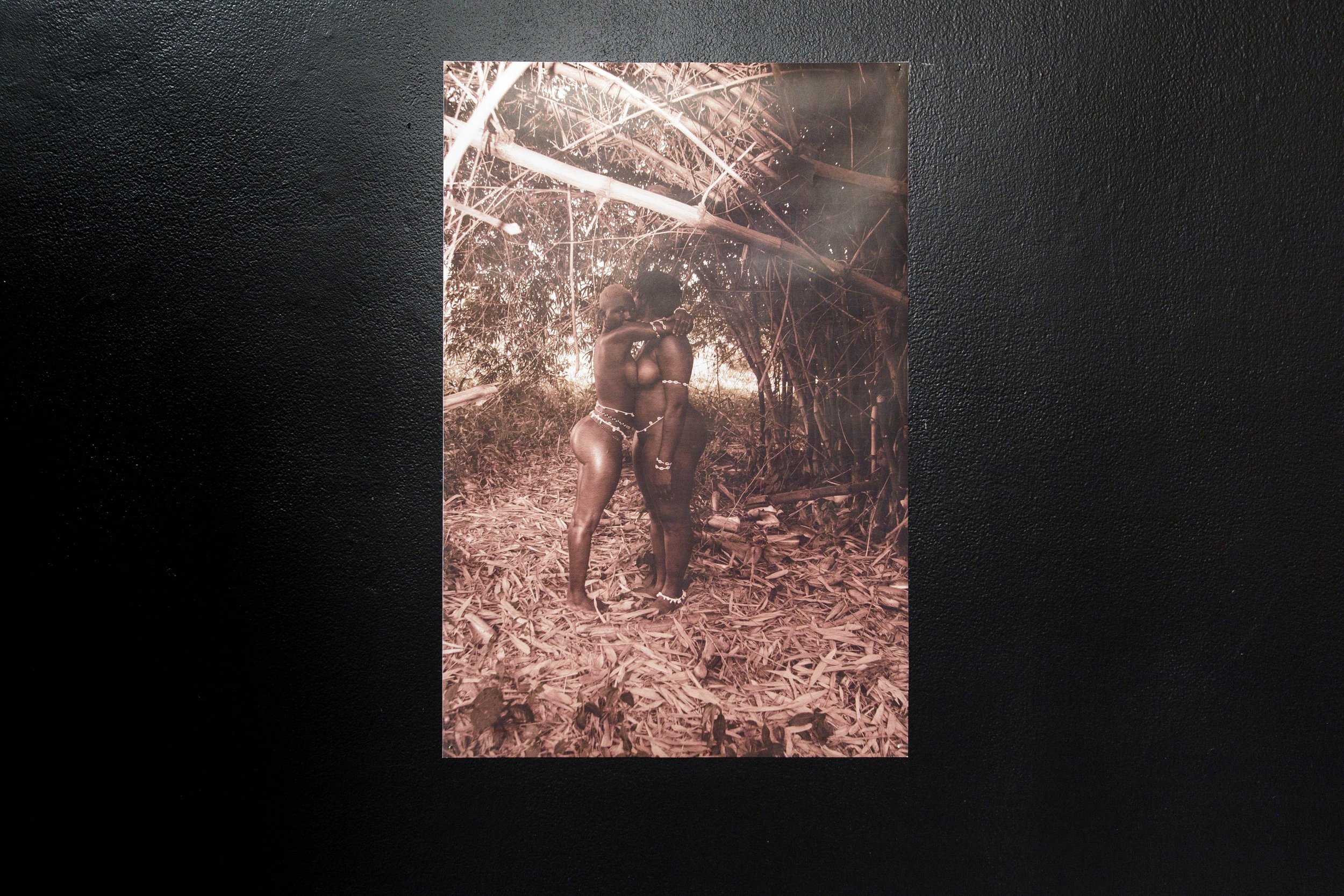

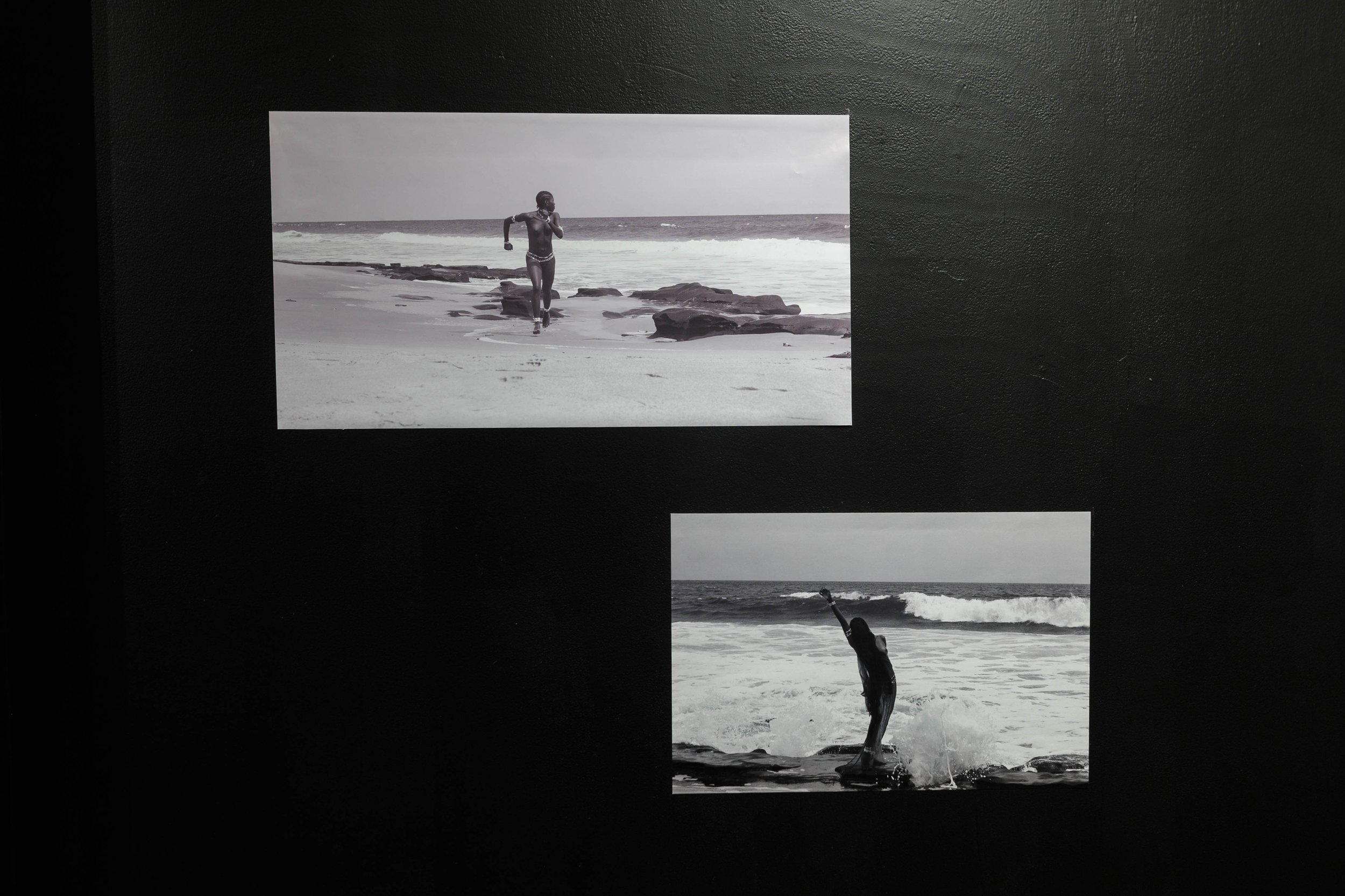

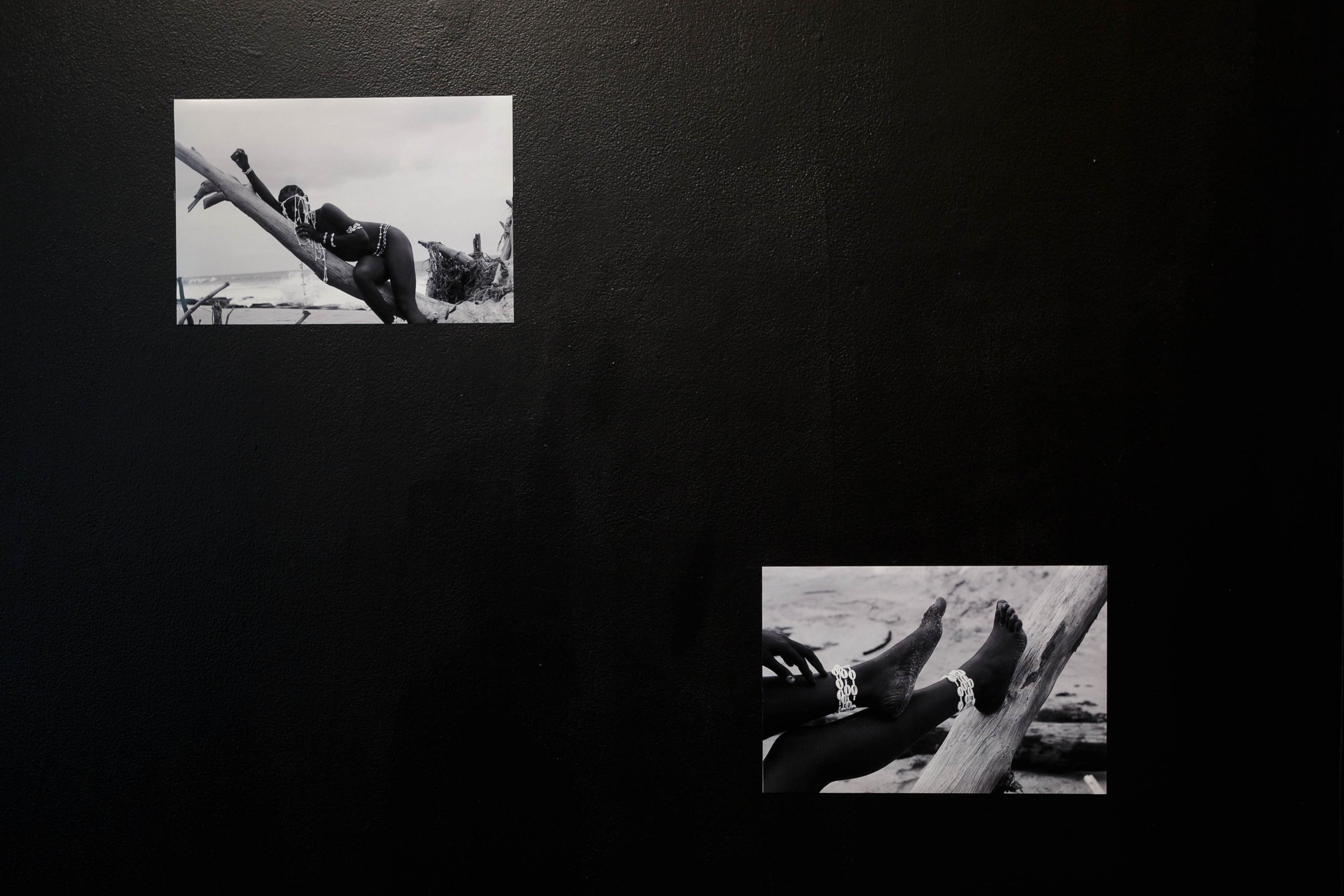

Abdulwasiu’s surreal work suspends the Black women in the frame, in time and history, by combining an active oppositional gaze and appropriating a style and aesthetics prevalent in photo ethnography. The Black female subjects are no longer the passive anthropological objects of a ubiquitous and voyeuristic white gaze; instead, they are posed as earnest subjects who have the power to look back at a gaze, defying stratification in an epistemological order that strips them of humanity and codifies their identities. By posing the subjects in her frame outside the definitive binaries of time and history, Abdulwasiu ardently cast interventions on the colonial recollection of the history of the Black female body. Through these vigorous acts of resistance, she reclaims the Black female body and envisions a present/future where Black women are able to roam the world freely and construct their reality in a way that pleases them.

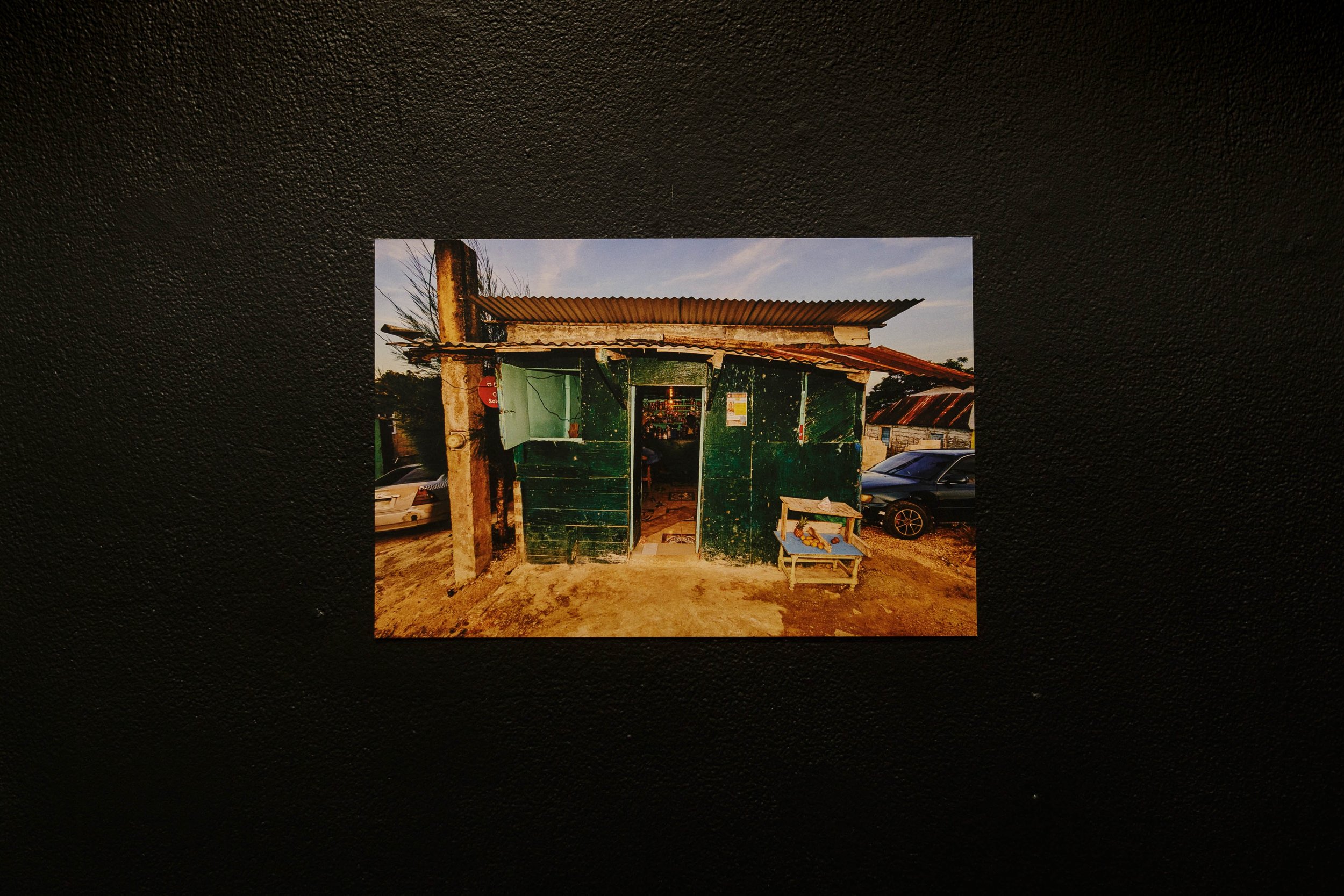

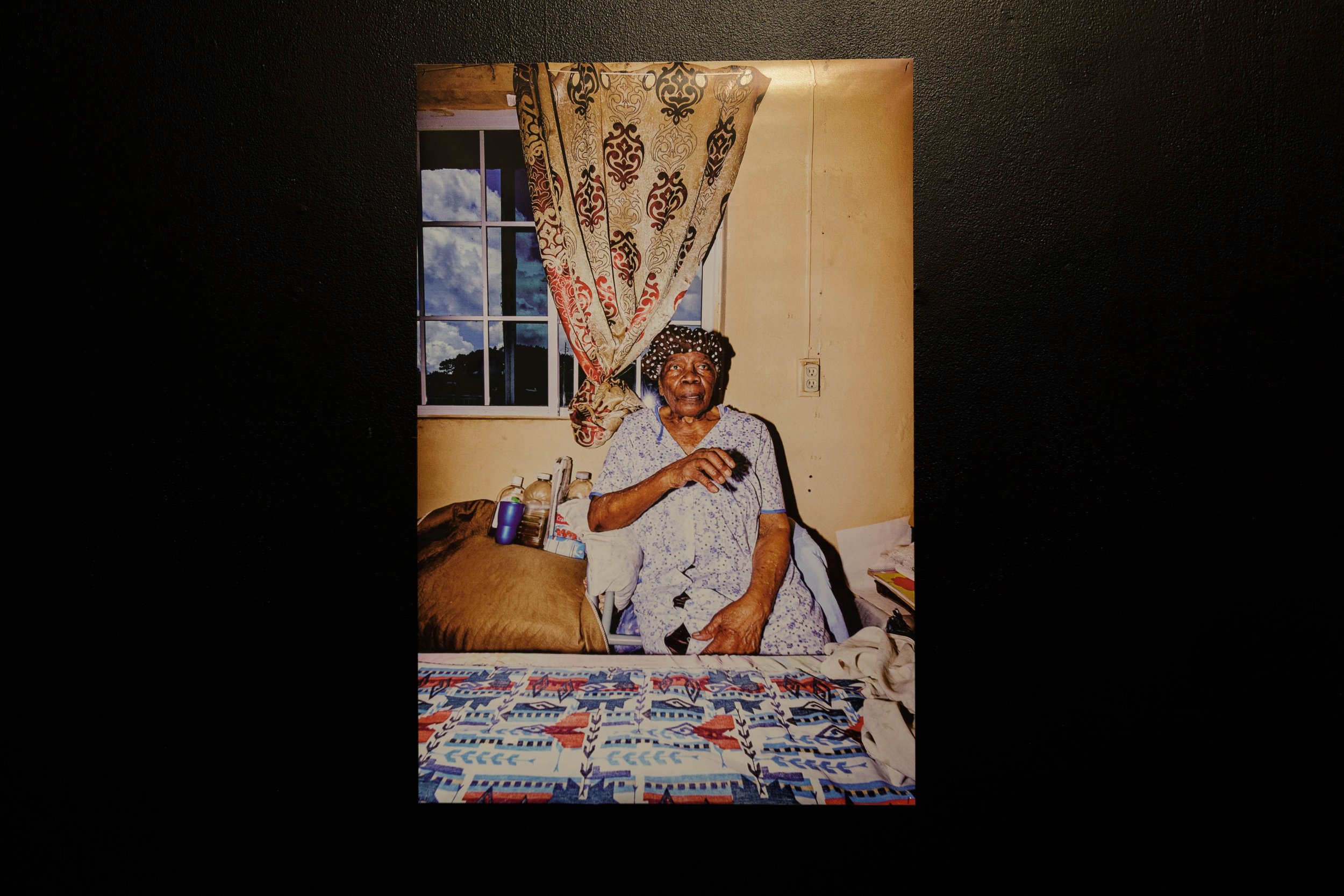

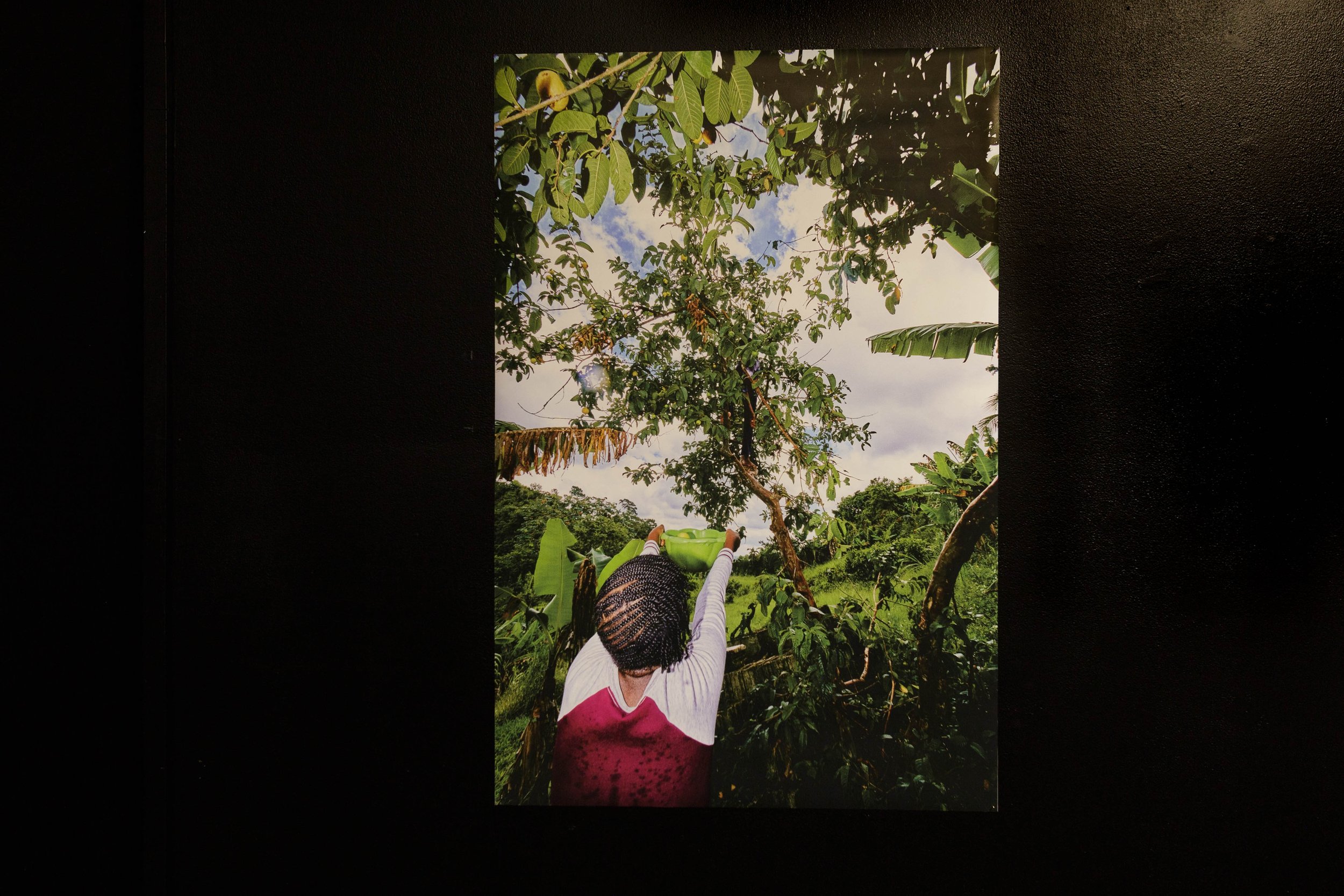

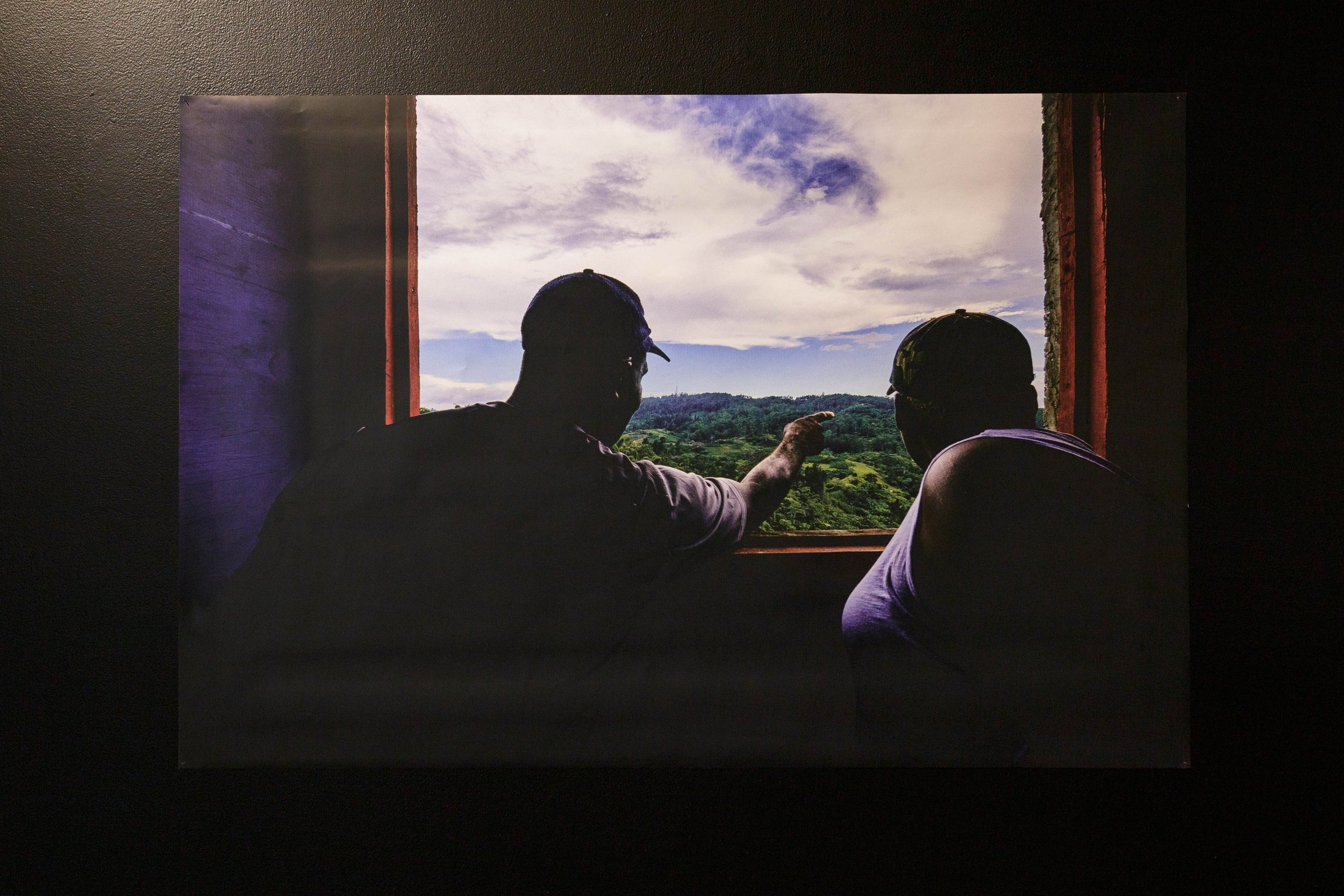

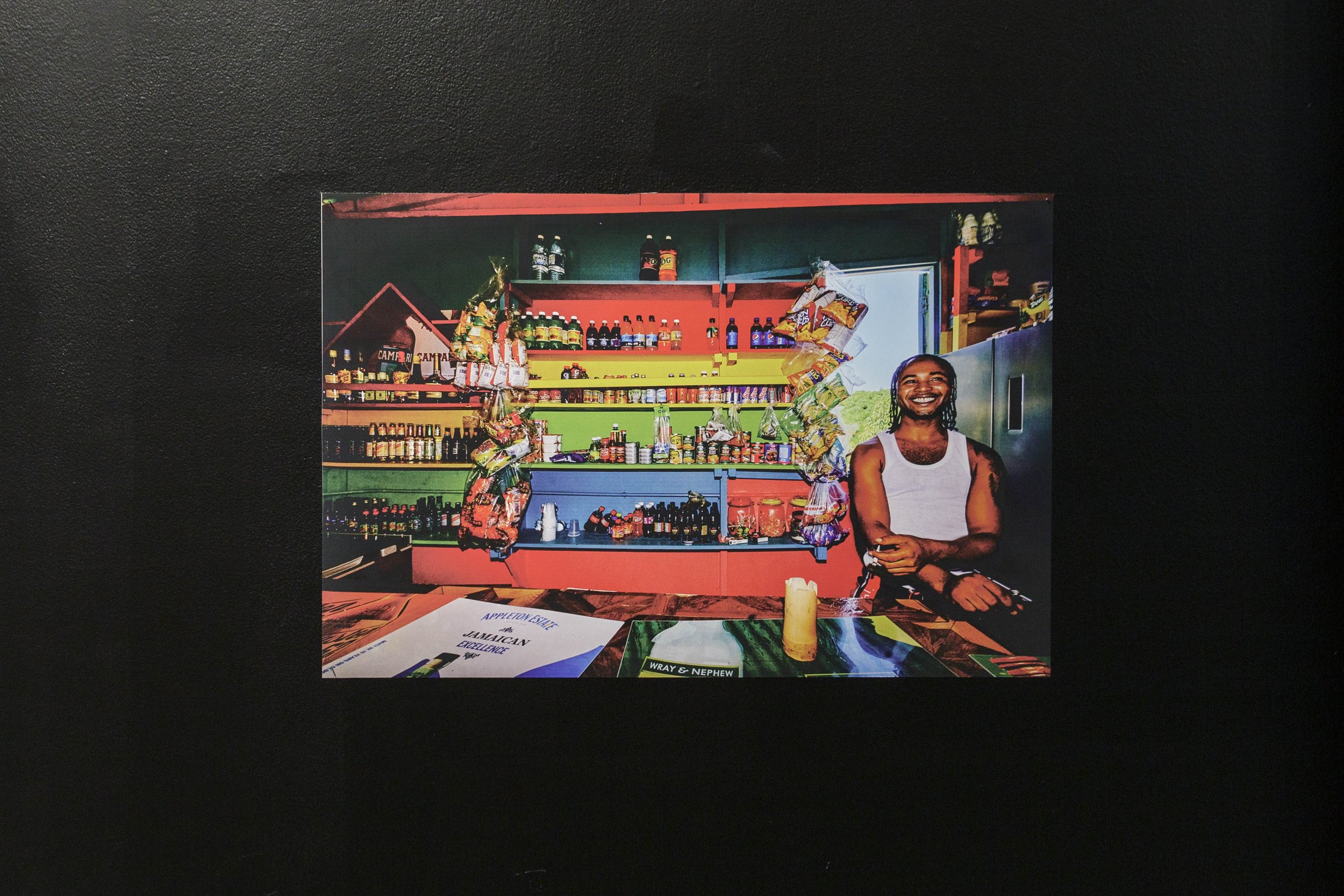

Chnarakis captures intimate shots of landscapes and people of post-colonial Jamaica; these images act as an active archive of the experiences and realities. This archive of Blackness is extremely important once one considers the history of forced servitude, disenfranchisement and dislocation that follows the Black bodies in Jamaica and most of the Caribbean islands. In the current archive of Blackness in Jamaica, most images pose the bodies under bondage and depict the landscape as a white man’s paradise. The prevalent archive of Jamaica was constructed by the white gaze to cater to the colonial imagination of Jamaica. In opposition, Chnarakis’ common, yet monumental images depict the Black subjects and landscape in the frame as emancipated, nuanced and intentionally present. Chnarakis’ works exist in line with Tina Campt and Micheal Foucault’s theories of Black refusal and agency; her images invite viewers to search for the things left unsaid and survey the margins, the gaps and the locations where Black agency and refusal can be found in the frame.

Abdulwasiu’s and Chnarakis’ images present different approaches to presenting the history of their bodies while also moving past that history and forging a deterritorializing sense of self. Lurking in the wings is longing; artists yearn for a reality that does not present itself in our milieu. Yet as they search and ruminate, they embody the most powerful form of refusal that could be undertaken by bodies labelled as the other, daring to envision and document a reality for Black bodies outside of the western dictated state of being and apprehension of Blackness.

Notes

1. Fred Moten poses Blackness as inherently fugitive and requires an ongoing refusal of standards imposed from elsewhere.

2. Tina Campt, A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See.

3. bell hooks, The Oppositional Gaze and Black Female Spectators & bell hooks, Aint I A Woman : Black Women and Feminism.

4. Tina Campt, Listening to Images.

Olumoroti George

Artistic Director

Click here for our Facebook Event

**Due to unforeseen circumstances this exhibition will now open Saturday / April 8th.

About the Artists

Abdulwasiu Salimat is a native of Offa, a town in Kwara State, Nigeria. Storytelling in her tribe is a Culture that passes down to all generations. It is how lessons are being learned and questions are being answered. Navigating into the world, she chose Science study of Earth in relation to Humankind, became a B.Sc. graduate of Biochemistry at the age of eighteen.

When she turned twenty, she saw the need to own up to her Being, her Color, and the spirituality in the Stories she originated from. In that honesty, Salimat learned photography in 2020.

In her philosophy, Truth is Fluid and the kind that she portrays is the one that reflects spirituality and bring the elements of nature in oneness to human. Her artistic practice preaches Nudity as a powerful Truth, a core Path to the Soul of a human. When Salimat is not speaking Yoruba, Nude photography is what she chose to tell her own part of the pain, the freedom, and the dynamic spectrum of Life, love and Death as an African woman. Now, Salimat is Twenty-three, a Scientist, a photo - Artist and a Film-maker that wears her diversity with surrealism.

instagram.com/abdulwasiu_salimat

twitter.com/SalimatAbdulwa3

Simone Chnarakis is a self-taught photographer born and raised in East Vancouver. Chnarakis comes from a second-generation Canadian-Jamaican family, her Jamaican roots inspire her artistic practice and her ever-growing sense of self and identity.

Chnarakis’s photography practice is rooted in capturing the beauty of Black people and moments of Black joy. Her practice exists in various realms; she is most notable for her event photography practice, where she captures dynamic moments of youth culture in East Vancouver. Her editorial works are entrenched in capturing the unique and diverse sense of style and self amongst her peers.

In Chnarakis’s artistic practice, she explores the nuances of mundane and intimate moments of Blackness through a post-modern and post-colonial lens. Through her exploration of mundane and familiar moments of Blackness, Chnarakis aims to raise questions about the interconnected nature of history, space, land, bodies and communal bonds in the construction of a Black identity that subverts the white gaze.

Exhibition Pictures courtesy of Sara Faridamin. Click here to visit her Instagram page.

Outro by Vanessa Fajemisin

As bell hooks explains, there is power in looking. A concept learned, either experientially or in so many words, by most Black children early on is that, looks can be confrontational, a sign of resistance, and even a challenge to authority. Though conversations of “representation” seem to dominate digital/social media today, being looked at and looking while Black has always been politicized.

But what does this say about the Black female gaze? A gaze most often developed within the context of traditional, hegemonic media that constructs our presence as absence, denying Black women in favour of ideals that deem that the women to be looked at, and thus desired or valued, are white (or as close to whiteness as possible).

In a culture firmly built on foundations of racism and misogyny (also see: misogynoir), the concept of “gaze”, who is permitted to have one, how and what they do with it, exists as the perfect microcosm for the oppressive systems and relations of power which inform, perpetuate and uphold these ideas. In her essay titled “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators”, hooks explains how the historic, systemic attempts made to repress Black people’s right to gaze has created within us an overwhelming longing to look, a rebellious desire, an oppositional gaze.

Stating, “By courageously looking, we defiantly declared: ‘not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality” , hooks explains how the ability to manipulate one’s gaze in the face of structures of oppression open up possibilities for agency. The “gaze” has long been a site of resistance for colonized Black people across the globe and in ‘Dialectics of Fugitivity’, Abdulwasiu Salimat and Simone Chnarakis demonstrate its use by exploring the power of looking beyond the past and into the otherwise from their perspective as Black women.

In her writing, hooks references the essay, ‘Black British Cinema: Spectator and Identity Formation in Territories”, by the author Manthia Diawara. Diawara identifies the power of the spectator, explaining that “every narration places the spectator in a position of agency; and race, class and sexual relations influence the way in which this subject hood is filled by the spectator.” In Dialetics of Fugitivity, Black female subjectivity is placed front and center as the works by Simone Chnarakis and Abdulwasiu Salimat mounted on the pitch black walls of Gallery Gachet reflect the inherent gestures of refusal that enters the frame when Black women play the roles of narrator, spectator and subject.

Through her work, Simone Chnarakis captures rich, warm, intimate shots of the landscapes and people of post-colonial Jamaica. These images exist as a powerful archive of lived-experiences, community, and Blackness in Jamaica, juxtaposing more common depictions of Jamaica and the Caribbean in general, that depict Black people as not much more than servers, workers and background props atop a white man’s paradise.Through rich, lively, straight-forward composition, Chnarakis challenges the history of forced servitude, disenfranchisement and dislocation and its depictions, offering viewers a look at a modern, emancipated Jamaica.

Alternatively, Abdulwasiu Salimat’s surreal work suspends the Black women she depicts in time and history, appropriating style and aesthetics common in photo ethnography to create an oppositional gaze unique to her experience of Black femininity and womanhood as a Nigerian living on the African continent. Blurring lines between sisterhood and Queerness, Salimat plays with obscurity, the Black female body monumentally present, yet somehow hidden throughout images and film. For Salimat, Black female subjects do not exist as passive anthropological objects for voyeuristic white gaze; but instead as subjects with the power to look back, subverting the colonial recollection of the history of the Black female body and reclaiming its agency and taking power back from spectators.

These images act as interventions on the oppressor’s archive and exist in staunch opposition to the dictated colonial state of being established in order to dispossess Black bodies of their humanity and agency. Through their works Salimat and Chanakris build on dialogue regarding the often posed questions surrounding the role of the artist in the construction otherwise and the politics that reside in an image. Their works exist beyond individual notions of Black representation in the arts and more so pose the Black female subjectivity as a political marker and an important tool that could be utilized in the quest to thoroughly emancipate the Black body.

Vanessa Fajemisin

About the Writer

Vanessa Fajemisin (she/her) is a writer, consultant and cultural curator living, working and playing on the shared, unceded, ancestral territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, also known as “Vancouver”. Passionate about all things arts, culture and media, much of her practice explores the intersections of art, digital culture, Blackness, girlhood, various subcultures and sociological theories. In addition to her role as senior writer for Tokyo-based magazine Sabukaru.online, Vanessa is a member of the Black Arts Centre, an artist-run centre in Surrey, BC, as well as the Black-owned, community-centred creative agency MADE BY WE (MBW). In her free time, she enjoys DJing, SUP and dog sitting.